- Home

- Paul Witcover

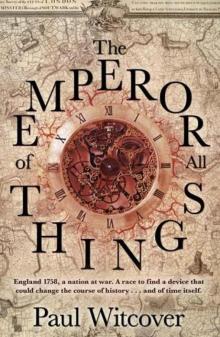

The Emperor of all Things Page 13

The Emperor of all Things Read online

Page 13

Quare sighed grimly and gave himself up to her ministrations. In a flash, she had helped him out of his coat and waistcoat, both of which looked to be quite ruined with blood. The shirt beneath was in even worse shape. After her initial assertiveness, Mrs Puddinge appeared uncertain how to proceed, as if it had been a long time indeed since she had undressed a man.

‘Can you …’ She motioned with her hands, a blush rising to her cheeks.

Quare stripped off the shirt, wincing at the pain in his shoulder. Mrs Puddinge, meanwhile, had gone to a table across the room, where there was a wash basin and a pitcher of water, along with some folded cloths. She filled the basin, grabbed a cloth, and carried them both back to the bed. Setting the basin down beside him, she wet the cloth and began to wipe the blood away. He winced again at her touch, light as it was.

‘There, there, Mr Quare,’ she said as she cleaned the wound, seeming to have recovered from her earlier upset, as if caring for another was the best medicine for what had ailed her. ‘’Tis not so bad, after all. A nasty gash, to be sure, but not a deep one. You’ll not be needing a surgeon to sew it up. Here … Press the cloth to the wound, just there – that’s right. I’m going to fetch some clean cloths to make a bandage. I’ll just be a moment.’

And with that, she bustled out of the room.

Quare got to his feet and crossed to the table from which Mrs Puddinge had taken the wash basin. There was a fly-specked square of mirror hanging frameless on the wall above the table, and Quare now angled himself so as to be able to see his back reflected in the glass. Specifically, the area between his shoulder blades, where Aylesford said he had stabbed him as they lay in Clara’s bed.

The indirect light from the window, coupled with the awkward positioning necessary to see anything useful, defeated him. He groaned in frustration. But he could at least examine his shoulder. Lifting the cloth, he saw a long, shallow gash; a sluggish upwelling of blood accompanied the removal of pressure. No doubt there would be a scar, to go with the one that Grimalkin had given him. He had never imagined that a career in horology would mark him so. He thought of the grizzled old soldiers he had seen in taverns, swapping stories and matching scars over glasses of gin. At this rate, he would soon be joining them.

‘Mr Quare, come back to bed this instant.’

He turned to see Mrs Puddinge glaring at him from the door, her arms bearing enough cloths to swaddle a small army. ‘A man would have to be foolish indeed to reject that invitation,’ he replied rakishly.

She blushed again, but couldn’t suppress a smile. ‘Get along with you.’

Once he was seated on the edge of the bed, she tended to his shoulder with practised efficiency, first cleaning the wound again, then placing a folded cloth over it, which she secured with a long strip of cloth wound about his torso. He had intended to ask her to have a look between his shoulder blades, but, as it turned out, there was no need.

‘Merciful heavens!’ she cried out.

‘What is it?’

‘Why, another wound. A worse one. Much worse! Can you not feel it?’

‘No. Or rather, a slight discomfort only between my shoulder blades, like an annoying itch I cannot scratch.’

‘That would be the scab. Here, let me show you …’ She fetched the mirror down from the wall and returned to the bed, where she held it at such an angle as to give him the clear view he had been unable to acquire for himself.

What he saw both shocked and fascinated; it felt strangely removed from him, or he from it, as though he were looking at someone else’s body, or, as in a dream, gazing down at his own from a superior vantage like a ghost or angel. Nestled between his shoulder blades was a blood-crusted incision no more than an inch long. The skin to either side was as purple as the petals of a violet, yet also streaked with scarlet and yellow and a sickly, algal green. It was a wonder that his fight with Aylesford had not reopened the wound. A clammy sweat broke out on his skin, and he felt as if he’d swallowed a knot of writhing eels.

‘Are you all right, Mr Quare?’ Mrs Puddinge asked in concern at his sudden pallor.

He took a deep breath and looked away. ‘I’m well,’ he said, but the croak of his voice belied it. Obviously, Aylesford had failed to pierce his heart with his knife thrust in the dark. But even so, Quare felt sure that a wound such as this should have done more than merely itch. It seemed the sort of wound one might see upon a corpse. Yet there was not even a twinge of pain. His heart was beating strongly, rapidly, and his lungs had no difficulty drawing breath. He didn’t understand it.

‘I’m afraid that’s beyond my poor skills,’ said Mrs Puddinge, shaking her head. ‘You’ll need a surgeon to sew that up, you will.’

‘I’ll have it seen to at the guild hall,’ he promised; now that he wasn’t looking at the wound, he was able to think more clearly, though the nausea showed no sign of receding. ‘Can you just bind it up for now?’

‘I’ll try, but God help you if it opens again.’ She set to work. ‘This is older than the one on your shoulder,’ she observed as she twined a strip of cloth about his chest. ‘You must’ve got it at the Pig and Rooster, a craven blow from behind, in the midst of the brawl.’

‘No doubt,’ he said. Perhaps it was the sensation of her hands upon the skin of his back, but he began to feel the stirrings of memory; or, rather, it was as if his body remembered what his mind could not. He began to tremble.

‘There, there,’ Mrs Puddinge repeated. ‘Almost done …’

No, it was not memory. More like the way he had seemed, upon being shown the crusted wound, to separate from his own skin. So now did he see in his mind’s eye the stark tableau, lit by moonlight, of himself and Aylesford pressed close on Clara’s bed in a travesty of intimate congress. He seemed to feel the other man’s body cleaving to his own, his hand clamped over his mouth; saw, or imagined that he saw, the wide eyes of Clara gazing at them, and then her knowing smirk as she turned away into shadows and tangled bed-sheets.

He rose to his feet and rushed to the open window, arriving just in time to spew the contents of his stomach into the alley below. Ignoring Mrs Puddinge, who, after an initial exclamation, had hurried to stand at his side, one hand stroking his arm, her touch like sandpaper despite her kindly intent, he leaned forward, arms bracing himself on the sill, closed his eyes, and let the cool city air – carrying its quotidian stinks of coal smoke and river stench and the waste of animals and human beings, odours that had sickened him during his first days and weeks in London, but which were now as familiar as the smells of his own body, and as reassuring – play over his face and torso. He was alive, damn it. Despite Aylesford’s efforts. And he had work to do.

Taking a breath, he straightened and pulled away from Mrs Puddinge. ‘I’d better have a look at Aylesford’s room,’ he said.

‘Shouldn’t I call for a doctor, after all?’ she asked, concern in her voice and in her eyes.

He shook his head. ‘Please, Mrs P. I’ve no time to argue.’ He crossed the room and pulled a clean shirt from amidst the scattered pieces of clothing Aylesford had strewn about in the course of ransacking his trunk. ‘There is more at stake here than one man’s health. At any rate, as I told you, I’m perfectly well.’ He turned away from her and drew the shirt over his head with a grimace, but schooled his expression to equanimity when he faced her again. ‘Now, if you will lead the way …’

‘Perfectly well, he says,’ Mrs Puddinge muttered as she preceded him out of the room, down the still-empty landing and up to the fourth floor. ‘With a hole in his back and a shoulder sliced open like a side of roast beef.’ She stopped before a door, produced her ring of keys from somewhere beneath her apron, and glared up at him. ‘You’re not a well man, Mr Quare. Deny it all you like, but the longer you do, the worse price you’ll pay. Heed your stomach, sir. It’s wiser than you are.’

‘The door, if you please, Mrs P.’

Scowling, she fitted the key to the lock. ‘Why, it’s unlocked!’ She pushe

d the door open. ‘Here you go, then, Mr Quare. I hope you find enough to hang—’

She broke off, and Quare pushed past her into the room, his hand on the pommel of his sword.

The room was empty, which was no more than he had expected. But it was not simply empty of Aylesford – it was empty of all trace of the man.

‘Why, his things … they’re gone!’ Mrs Puddinge said from just behind him.

‘What things?’ he asked, turning to her.

‘He had a small trunk that he carried in on his shoulder last evening,’ Mrs Puddinge said. ‘It was still here this morning – I’m sure of it. He … Oh, dear Lord in heaven!’ She looked as if she might faint, and Quare reached out to steady her. ‘There on the floor!’ She pointed with the hand that held the keys; they rattled with her shaking. ‘Blood, Mr Quare! He must’ve come back here after he fled your room! He must’ve come back here and waited until you had satisfied yourself that he was gone from the house! Then, when you returned to your room, he must have taken his trunk and crept out of here as quiet as a mouse!’

Quare felt close to fainting himself. Mrs Puddinge was right. The drops of blood on the wooden slats of the floor confirmed it. He’d assumed that Aylesford had escaped into the bustling streets, but instead he’d retired here, to this room, biding his time until Quare had given up the chase. Then – he could picture it as clearly in his mind as if he’d witnessed it himself – he’d hoisted his trunk onto his shoulder and left … along with any evidence that might incriminate him or shed light on his mission. Quare cursed – he had badly misplayed the situation. Master Magnus would not be pleased.

Master Magnus!

Aylesford had said the master was dead. Murdered in the night, like Mansfield and the rest. Quayle prayed to God that it was a lie, but he was forced to admit that everything Aylesford had told him this morning had thus far turned out to be true. He had to get to the guild hall.

Mrs Puddinge, meanwhile, was edging into hysterics. ‘Why, he could have slipped back into your room while you were searching the street outside and slit my throat! Or when I went to fetch bandages, I might have met him in the hall or on the stairs, and what then? Oh, Mr Quare, he might still be lurking about, waiting for the chance to finish me off!’

‘I’m sure he’s not,’ said Quare. ‘He’s gone to report back to his masters, just as I must do.’

‘No,’ she shrieked, grabbing hold of his arm. ‘You can’t leave me! He’ll kill me, he will! Just as he did those poor young men!’

‘Mrs Puddinge,’ Quare said as forcefully and yet calmly as he could, ‘Aylesford has no interest in harming you, I assure you.’

‘Oh, aye, like you assured me I would be perfectly safe when you went gallivanting off after him!’

Quare felt his cheeks flush. Damn it, the woman was right. He had left her in danger. Once again, as in his confrontation with Grimalkin, he was forced to admit that he was ill-prepared for this game in which he suddenly found himself immersed right up to his eyeballs. He knew that he was lucky to have survived this long. And, no thanks to him, so was Mrs Puddinge. Nevertheless, he felt certain that Aylesford was long gone, and that Mrs Puddinge was in no further danger. ‘It’s me that he’s after,’ he told her now. ‘But if it will set your mind at ease, I’ll look for other lodgings as soon as I’ve spoken to my masters.’

‘What, so that you can put some other innocent at risk? But even if you were to move out, Mr Quare, he still knows that I know he’s a French spy,’ Mrs Puddinge pointed out, not unreasonably. ‘He’ll still have cause enough to want me dead!’

‘Once I’ve exposed him, the whole guild will know – and my masters will see that the news reaches the ear of Mr Pitt himself. Will Aylesford kill us all, then? Don’t you see, Mrs P? The more people who know, the safer we are. Your surest protection lies in my getting to the guild hall!’

She pondered this for a moment, then nodded, a look of steely determination on her face, where, just a moment ago, he had seen only terror. ‘I’m going, too, Mr Quare.’ And, before he could object: ‘I won’t sit here all alone, waiting patiently for my throat to be cut. Say what you will, but you can’t know for certain that he’s not lurking about somewhere close by, watching and waiting like a cat at a mouse hole. As long as he sees that we’re together, he’ll not dare to strike. And if he sees us both go to the guild hall, he’ll know the jig is up, and that it will avail him nothing to creep back here in the dead of night and silence me.’

Quare could not fault the woman’s logic. ‘Very well, but we must make haste. Give me a moment to clean myself up and finish dressing, and we’ll go together.’

‘I’m not letting you out of my sight,’ she declared.

In the end, he prevailed upon her to allow him a modicum of privacy, standing with her arms crossed and her back to him just outside his cracked-open door. After dumping the bloody water out of the window and refilling the wash basin with the last of the fresh water from the pitcher, he undressed and hurriedly wiped the worst of the blood, grime, and sweat from his skin, shivering all the while. Then he dressed more quickly still, pulling fresh linen and clothes from the floor. He drew his hair back in a tight queue. His coat, if it were even salvageable, which he doubted, required more time and attention than he could spare just now, and so he wore only a waistcoat, once blue but now so threadbare and faded that it merely aspired to that colour. He tucked his spare hat, a battered tricorn, under one arm.

‘Well?’ he demanded of Mrs Puddinge at last. ‘How do I look?’ He did not want to draw unnecessary attention on the streets.

She opened the door fully and regarded him with a critical eye. ‘I shouldn’t care to present you to His Majesty,’ she said at last, ‘but I suppose it could be worse. Have you no spare coat?’

‘Such luxuries are beyond a journeyman’s purse, Mrs P.’

‘Why, ’tis no luxury! Here, now, I’ve still got my husband’s second-best coat – I buried him in his best, God bless his bones. I believe it will fit you very well indeed. Come along while I fetch it.’

So saying, she started off down the landing; her own rooms were on the ground floor of the house. Quare closed and locked the door to his room and followed her. At the top of the stairs, she paused and waited for him to catch up. ‘I’ll feel safer if you go first, Mr Quare.’

He nodded and slipped past her, descending with caution, his hand on the pommel of his sword. But, as before, he encountered no one. Mrs Puddinge unlocked the door to her private chambers, and again Quare preceded her inside, checking to make sure Aylesford was not hiding there. Only when he had searched every inch, including under the bed, did she deign to enter. Then, brisk about her business, she bustled to a trunk, threw it open, rummaged inside and drew forth a drab brownish grey monstrosity of a coat. This relic of a bygone age she unfolded and let hang from one hand while beating the dust from it with the other. Quare found it difficult to believe this garment had been anyone’s second-best anything. He would have been embarrassed to see another person wearing it, let alone himself. It seemed to have been stitched together from the skins of dried mushrooms. He sneezed, then sneezed again more violently, as an odour reached him, redolent of the ground if not the grave.

‘Here you go, Mr Quare,’ said Mrs Puddinge, advancing towards him with the mouldering coat extended before her like a weapon. ‘Not the height of fashion, I know, but sufficient unto the day, eh?’

He eyed the thing with something like horror. ‘Er, I can see how much the coat means to you, Mrs P. As a keepsake of your late husband, that is. I couldn’t possibly take it.’

‘Stuff and nonsense,’ she insisted. ‘I won’t have one of my young men walking about the streets without a coat. What will people think?’ She pressed it upon him again, and, after setting his tricorn upon his head, he reluctantly took it.

‘Got a bit of a smell,’ he suggested, holding his breath.

‘Beggars can’t be choosers, Mr Quare,’ she responded, as if offended by hi

s observation.

Quare bowed to the inevitable with a sigh. He advanced his arms through the sleeves, half expecting to encounter a mouse or spider. Perhaps a colony of moths. The coat proved to be a trifle large, even roomy. It settled heavily across his shoulders, and the stench of it was like a further weight. He didn’t think he could bear it. Yet before he could say another word, there came a sharp rapping at the front door of the house.

Mrs Puddinge shot him a fearful look.

‘That must be the watch or, worse, the redbreasts,’ he said in a low voice. ‘Quick, Mrs P – you delay them, and I’ll go out through the window. You can stay here; you’ll be safe with these men.’

‘I’ll do no such thing!’ Even as she spoke, she was crossing the room to a casement window looking out on the same alley as the window in his room above. She quickly threw it open, then turned to him as another round of hammering began at the front door. ‘We’ve no time to argue, Mr Quare. Are you coming or not?’

Again he seemed to have no choice but to accede. Beneath her matronly exterior, Mrs Puddinge was a force to be reckoned with. Quare helped her over the sill and out of the window, then followed, pushing the glass-paned wings closed again behind him.

It was a chill, grey day, with more than a taste of encroaching autumn. Despite the lateness of the hour – nearly eleven by his watch – tendrils of fog snaked through the air, obscuring the sun and congealing in pockets along the cobbled pavement of the alley.

‘What now, Mr Quare?’ Mrs Puddinge asked, eyes shining beneath her bonnet, for all the world like a girl swept up in a childhood game.

‘Now we make for the guild hall,’ he said in a low voice. ‘We’ll go this way, up the alley, away from your house. Once we reach Cheapside, we’ll blend in with the flow. Just act naturally, Mrs P. Don’t hurry or do anything that might draw unwanted attention.’

‘I confess I am rather enjoying this,’ she confided as they walked up the alley side by side, avoiding as best they could the night’s detritus thrown from upper storeys. The stench was enough to make him glad of the second-best coat, whose dank odour, however unpleasant, was preferable to that of offal and excrement. ‘Why, it’s as if it were five years ago, and Mr Puddinge still among the living! Many the morning I would walk him to the guild hall, he wearing the very coat you have on now, the two of us talking of everything and of nothing, happy as two peas in a pod!’ As they reached the end of the alley and turned into the bustling thoroughfare beyond, she slipped her arm through his, giving him a warm smile, which he could not help but return.

The Emperor of all Things

The Emperor of all Things